In May of last year, Allison Miller began drawing bold capital letters freehand on paper in black acrylic, cutting them out and photographing them in the landscape: R among banana leaves, S amidst poppies, P suspended on the branch of a copper tree. She then brought the letters back to her studio and glued them down on paper, accompanied by free mark making and strongly-colored grounds. D, A, P, Q, R, S, M, and E all appear.

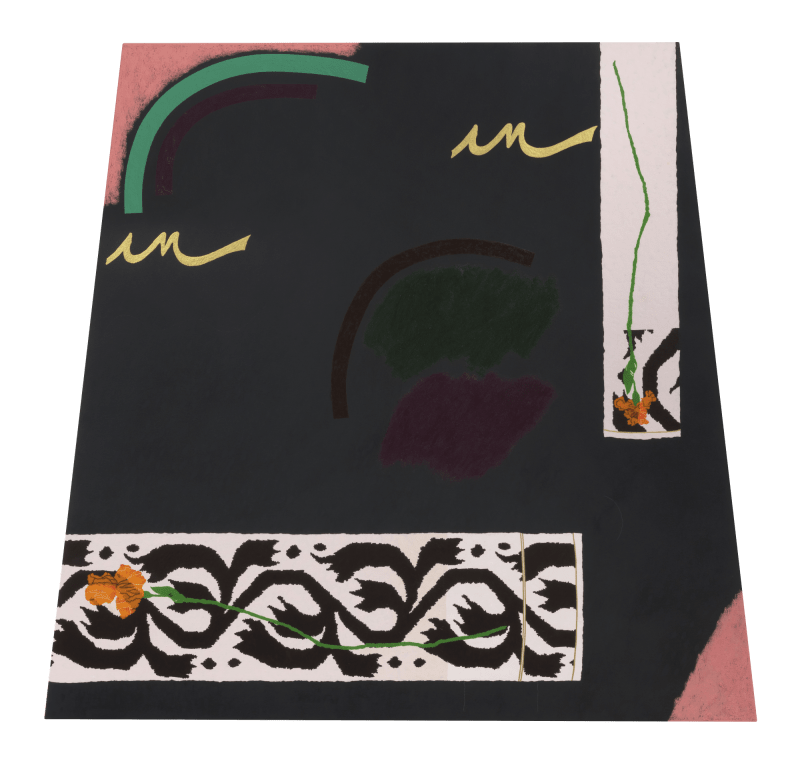

In earlier works, Miller used forms that might evoke worldly references in the same way we see animals and other shapes in clouds, but her paintings have never included anything so explicit or concrete as a letter of the alphabet. Such elements began creeping into her lexicon in her 2019 solo show at The Pit in Los Angeles. In that exhibition, Miller used excerpts of her mother’s handwriting, arrow icons resembling those on our computer screens, and a diagrammatic spider web. Now, in this latest body of work, representational moments are in evidence throughout, including letters, handwriting, roses, irises, a crescent moon and a spider web. The recognizable imagery that began as a trickle in 2019 gained force in early 2020 with the letters placed in nature, and is now a strong presence alongside the abstract language Miller has long established.

It is difficult these days not to see everything through the lens of the pandemic, but that viewpoint offers some insight into how the new paintings might operate. Covid-19 has denied us direct engagement with the world, and in the face of this lack, Miller’s increased use of referential forms may function to restore some sort of presence through symbolic means. The iconography in the new work speaks to circumscribed experience: a moon may be seen through the windowpane, spider webs appear in the corners of the house, and Miller’s rose is not painted perceptually, but is instead a symbol.

Replete with bright, clean hues, just about every painting includes flowers in some form, whether in printed fabrics, painted images or curving lines that twist like floral tendrils. The plants that served as armatures for the handmade letters Miller photographed in May have now found pictorial incarnations. Similarly, letters and handwriting are formal objects as well as vehicles of mediation: they communicate a writer’s experience, but through the filter of language. The new paintings’ use of recognizable imagery demonstrates art’s ability not to replace the world, but to encapsulate experience and make it tangible, and thus available for remembrance, reflection and reaction.

Rendering experience tangible does not, however, make it entirely comprehensible. One of the signal qualities in Miller’s work is her use of graphic clarity to effect profound mystery. The visual elements of her paintings are crisp and unambiguous, but they never resolve into a clearly interpretable message. In fact, the works become systems for the disruption of meaning through a series of spontaneous improvisations that build each painting from start to finish. This is exemplified by “Mirror,” a pyramid of letters repeating like a code, hovering above a receding dark violet plane that suggests the mouth of a great pit, presided over by a crescent moon made from flower-printed fabric. The image is cryptic in the extreme, and compelling in equal measure. Even the shape of each canvas is slightly jarring: the paintings are trapezoids, just a bit off the rectangle. This is a shape Miller has visited before, as both an element within paintings and the geometry of the canvas itself, and it emphasizes her interest in painting as a simultaneous object and illusory window. These divergent elements are knit into a visually stable and powerful whole through Miller’s formal sensitivity and a knack for unexpected balance.

With these new works, Miller strategically places us in a stream of consciousness where everything defies expectations and no definitive meaning locks into place. Continually evading definition, Miller’s paintings liberate themselves and the viewers to integrate all manner of experience, from loss and fear to joy and love. Her work opens ever outward, helping us to ponder and face our own unknown futures.

— Daniel Gerwin

ALLISON MILLER (b. 1974, Evanston, IL) lives and works in Los Angeles. She holds a BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design and an MFA from the University of California, Los Angeles. Miller’s work can be found in the collections of the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, the Orange County Museum of Art, the Pizzuti Collection, the West Collection, the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, and the Neuberger Museum of Art. Her work has been reviewed in Artforum, Frieze, the Los Angeles Times, Modern Painters, The Brooklyn Rail, Hyperallergic, and Flash Art. Recently, Miller discusses acquisitions by the Loeb Art Center with curator Mary-Kay Lombino and conducts a studio visit featuring the work for Upside Down Pyramid with Daniel Gerwin hosted by the Neuberger Museum.

Related artist

- X

- Tumblr